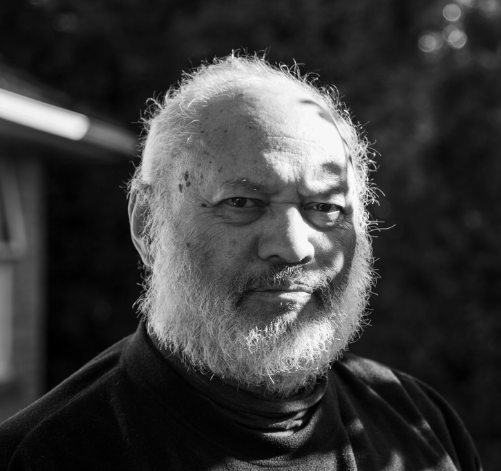

Two worlds coming together –

”“Māori voices are being listened to more over time.”

– Rereata Makiha

The understanding of our physical environment and how or why natural events occur have intrigued scientists since the beginning of time. However, centuries of acute observation, living on the whenua (land) and the accumulated wisdom of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and Maramataka (the Māori lunar calendar) cannot be overlooked when it comes to better understanding our environment. And according to Rereata Makiha, the Western world is increasingly listening to the centuries of knowledge that Māori gained since landing in Aotearoa over one thousand years ago.

Matua Rereata Makiha is an environmental tohunga (expert) who holds an impressive repository of te ao Māori environmental wisdom. Rereata continues to add and validate new sets of scientific evidence for mātauranga Māori and, in recent decades, has been working alongside rangatahi Māori and Western science to share that knowledge and ensure it carries on through future generations. At the heart of his research is the vital mahi (work) of capturing, recording and archiving the near-extinct environmental knowledge he has gained for future generations to embrace, honour, practise and pass on.

Over the past five years Rereata has been leading Te Pupuhuka a Tai, an initiative that supports Māori-led science and innovations to guide eco-restoration, share knowledge and revitalise te reo. It is a whānau-centred restoration project, spanning several haukāinga (local people of a marae) within Te Tai Tokerau/Northland. Beginning in 2018, Matua Rereata and a small team of volunteers from their haukāinga set out to empower whānau to be the key researchers of the taiao (natural world/environment) in their rohe.

The mahi has been observing and monitoring the takeke (piper fish) and other fish-related species that live in the estuary where fresh water meets saltwater, and learning about the intricate ecosystems associated with the taiao. Whānau have monitored the taiao, made extensive observations, collated data, and confirmed several significant findings.

”“In our old Māori world, we look at tūhononga: everything is connected.

One thing does not happen on its own — there’s other things around it that cause it to happen."

“We have been collaborating with Western scientists and academics too,” Rereata says. “One day when some scientists were due to visit the estuary, our young ones told them, ‘You don’t want to go down today, today is a Huna day (bad day, everything is hidden) and you’re not going to see anything!’ So, they went down… and they saw nothing — the young ones were right.

“It struck us that if a team had researched the estuary based on that day, what kind of report would they have provided? So, our team compiled a video of the Tangaroa Kiokio day (good day, fish are running) in the same area and you should have seen the activity — oh such a difference!

“We got them to concentrate on the Tangaroa Kiokio days and then compare them to the other days and they’ve made some brilliant findings,” he says.

“When you want to check when the takeke are coming in, you watch the flowering of the pōhutukawa and matatiti muramura phase of summer in the morning. We correctly predicted this is when the takeke eggs will come ashore — it happens only for a brief period, a matter of minutes each year.

“In our old Māori world, we look at tūhononga: everything is connected. One thing does not happen on its own — there’s other things around it that cause it to happen. The academics and scientists come off a different information stream, so we are sharing our knowledge and findings with Western scientists.

“But our rangatahi trust their maramataka so much you cannot turn them — they will not be swayed by anyone. They can tell you when distinct species of fish are going to be running in the kurutai. They have the pattern down, they have got it right and they understand it.

“We are doing research in the reporepo with Hawaii too. Our team were up in Hawaii sharing their findings when I sent them a photo of this pōhutukawa tree that usually flowers from the east facing the sun, then to the north. But last year, on 2 December, it flowered west to south, the total opposite,” he says.

“So, we got online and had Zoom meetings together trying to figure out why that was. We held a wānanga calling on some of our old tupuna whare wananga kōrero and they produced the theory that floods are coming. They asked themselves when they are most likely to happen. And they pegged it to the Tamatea days in January. This got them quite worried and a week before the floods that caused major damage in Aotearoa in January, they travelled from Hokianga to their whānau in Hamilton to warn them of potential floods. They even got them to cancel the outdoor activities they had planned. These are kids just out of school.

“Sure enough, the floods came and caused major damage right across the country, but their whānau and community were ok because they had warned them about the floods. That is how brilliant these rangatahi are, trusting in their tupuna, maramataka and kōrero tuku iho — and this is the type of mahi that The Tindall Foundation has been funding us to do. It is invaluable.

“There continues to be a series of unanswered questions that require ongoing observations and further exploration and examination — we never stop learning. But sharing and passing on the knowledge we have, and the knowledge we gain along the way is vital.

“It seems to me that scientists are slowly catching up and Māori voices are being listened to more over time. I am confident our rangatahi have grasped this knowledge and they are applying their own way of learning and remembering it.”

The sharing of the Western and Māori world learnings is an inclusive and mutually beneficial way to help understand our natural environment better and Matua Rereata Makiha is helping lead the way.

Photo credit: Cornell Turiki